Taft is one of the luckiest places in that Heads of School tend to stick; the school is on its sixth ever head, Mr. Becker, in its 135th year of operation. I bet most students could name at least three, if not four, of the Heads: Mr. Becker, for obvious reasons; Mr. Mac, as his last year coincided with the class of 2026’s first year; and probably Mr. Taft himself. Each name has established itself on campus—each Head of School honored with a location that has worked itself into the everyday vernacular of Taft students, ensuring their legacy lives on.

Lowerclassmen boys live in HDT. Soccer and lacrosse play under the lights on MacMullen Field. Tafties dressed in red head up to Cruikshank Gym (named after Head of School Paul Fessenden Cruikshank) to cheer on volleyball and basketball, or don their coats in the winter for the chilly trek to Odden Arena (after the one and only Lance Odden) to support the hockey teams. But, as some might have already noted, I’ve mentioned five names, not six.

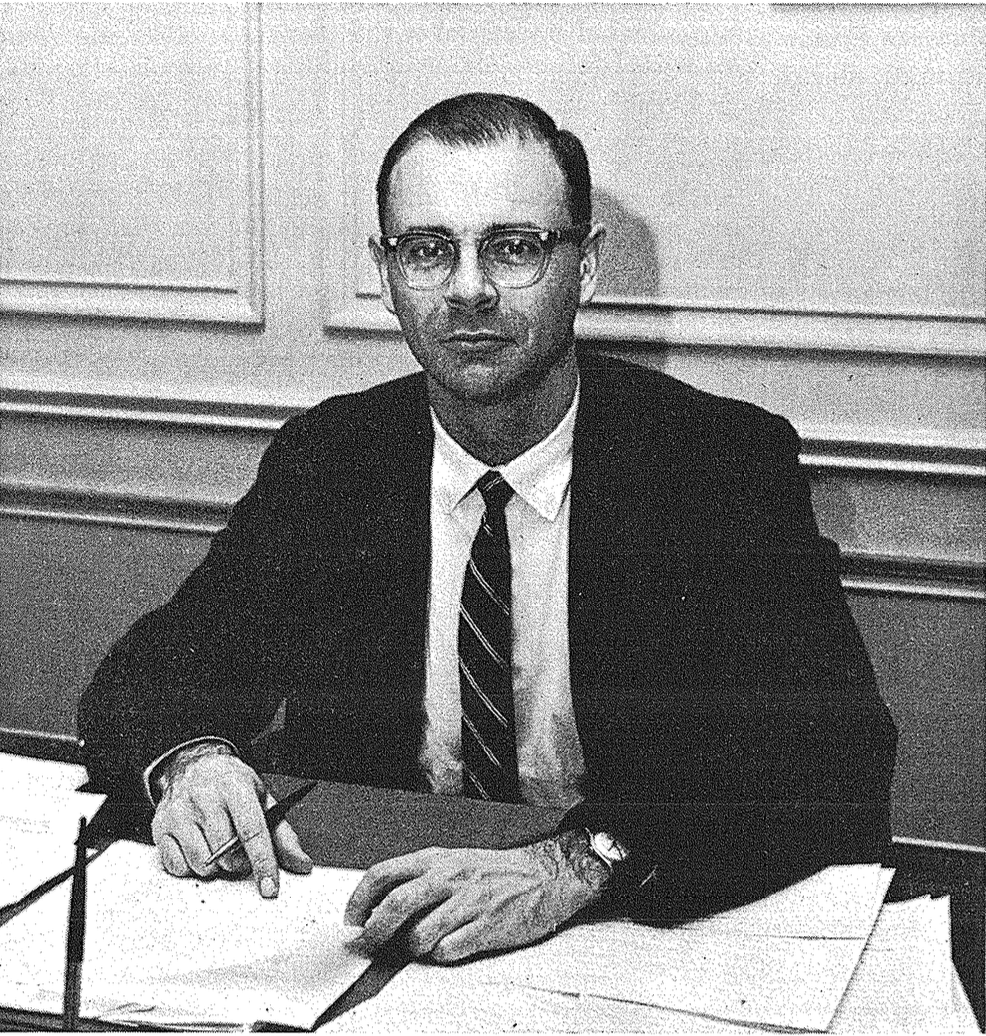

The sixth and final Head of School, Mr. Esty, does, in fact, have a building dedicated in his honor, just not in his name. Centennial, an upper school girls’ dorm, was donated for the 100th year of the school’s operation and dedicated to Taft’s third Head, Mr. Esty. Mr. Esty served as Head of School from 1963 to 1972, guiding Taft through one of the most tumultuous decades of the 20th century and navigating periods of immense change in the country and within the Taft community itself. Despite his tenure being the shortest of any Head of School, The Papyrus published in 1964 that “Mr. Esty has affected them (the students) and the school in an extraordinary fashion” (1964, Issue 4).

Mr. Esty began his time at Taft after serving as an admissions dean and instructor in mathematics at Amherst College. He firmly believed that Taft should

“provide a firm intellectual and social structure as a base of security for an increasing number of forays into new knowledge and new awareness of self… We must seek new insights, admit new knowledge, experiment with new methods, and be willing to accept new forms of old truths.”

There was no better example of this ideology than Mr. Esty himself.

In November of 1963, Mr. Esty journeyed to Washington, D.C., to testify before Congress in an attempt to stand against forced conscription as a principle. He argued that the basis of the draft was simply “filling the Cold War garrison,” and thus unnecessary (Papyrus, 1963, Issue 7). In addition to his two testimonies before Congress, he also published his work in the New York Times. His article, entitled “The Draft: Many Threatened, Few Chosen,” detailed the process and statistics behind the selective service. He remained steadfast in his beliefs, continuing his political advocacy during his time at Taft (Papyrus, 1963, Issue 7).

As Taft’s third Head of School, there were big shoes to fill and high expectations from students and faculty alike. Mr. Esty considered these expectations but worked diligently to uphold his principles and moral values, aiming to preserve tradition while shaping Taft for an ever-changing and modernizing world. When change struck the country, Mr. Esty was there to address it. He led a special Vespers, along with the chaplain at the time, in November of 1963 following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, sending a message to the heart of the student body that, “neither death nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor powers… nor any other creature, shall be able to separate us from the love of God” (1963, Issue 9).

In addition to his focus on national events, he spent much of his time dedicated to internal developments, furthering his goal of fostering an ambitious, interdisciplinary education. Mr. Esty established the counseling department at Taft, hiring the school’s first-ever psychiatrist to help students manage their “emotional health problems” (1963, Issue 13). His genuine care for students and their success, both at Taft and beyond, was evident in the work he did daily to improve opportunities and quality of life for everyone on campus.

He not only fostered students’ mental health but also their intellectual curiosity. Mr. Esty established the Independent Studies Program (ISP), which continues to this day. When the program was founded, The Papyrus wrote:

In reviewing Mr. Esty’s policies and changes, several undercurrents of thought become apparent. His desire to instill in the student the desire to learn and his hope that the student will evidence some interest in teaching himself are illustrated by his institution of the Independent Studies Program.

Mr. Esty strived to create a school where ambition could become palpable and dreams a tangible reality for all, students and teachers alike. During his tenure, he also established a sabbatical program for faculty, serving as an example of his belief in exploration and learning at every level.

Perhaps the most noteworthy change Mr. Esty worked on during his time at Taft was the integration of female students in the fall of 1971. After working diligently to plan for the adjustment of increasing the student body, female students were officially enrolled at Taft the last Fall before his departure in the Spring of 1972. Such an instrumental change was not taken lightly. Mr. Esty worked with committees and the Board of Trustees to ensure a smooth transition, wanting to lay the foundation for how the school would grow and adapt after him.

There is no better way to describe Mr. Esty’s actions and intent than to say he wanted to leave Taft better than he found it. From massive shifts in the demographics of the school to smaller changes, like expanding senior radio privileges to include more hours, the scope of his influence touched every layer of the Taft experience. Reflecting on his tenure, Mr. Esty said it was “the richest, fullest, and happiest my wife, four sons, and I had ever known” (1971, Issue 5).

Mr. Esty may not have served the longest time at Taft, but his impact, quiet yet strong, has left an impression that endures to this day. Despite his numerous accomplishments and the high regard of his peers, Taft students in 2025 don’t remember Mr. Esty in the same way we reference Odden or Cruikshank, because his name and story have blended into the foundation of Taft itself.

We walk along the bricks with the names of every graduating class every day on our way to Wu, maintaining the silent power that comes from recognition. These names, and those of the Heads of School before and after him, are an integral part of what we consider to be Taft; why isn’t Mr. Esty? His legacy deserves to be honored, like all who came before and after him. So we have to work to keep his memory alive: share stories of his work, live in his legacy, embrace his philosophy of engaging with passion and ambition, and most importantly, say his name: John Cushing Esty.