I was not expecting to spend my Tuesday night in C118 delicately balancing dry spaghetti, masking tapes, twine, and a marshmallow – but there I was, at 9 pm, building a pasta tower with Tatum ‘26, Omar ‘26, and Lincoln ‘26 under the watchful eye of Mr. LaCasse. It was part of this year’s leadership training for dorm monitors, and our goal was to create a structure somewhat reminiscent of the Eiffel Tower. What we ended up with looked slightly more like a hayseed swaying in the wind: spaghetti held together by a little masking tape, and a lot of hope. We tried, and ultimately succeeded, in keeping our structure from falling over, but the exercise prompted me to reflect on what structure looks like within leadership. Is there a “perfect structure” for student government here at Taft?

The Student Handbook defines the “central agency of self-government at Taft as the monitorial staff, a group of 12 to 16 seniors elected by their class. The school monitors implement the Honor System, assist in the supervision of the dormitories, and accept a large share of the responsibility for the day-to-day conduct of the school’s affairs.” Ultimately, Taft’s definition of leadership is “choosing to act with empathy, integrity, and courage to help one’s group achieve its goals.”

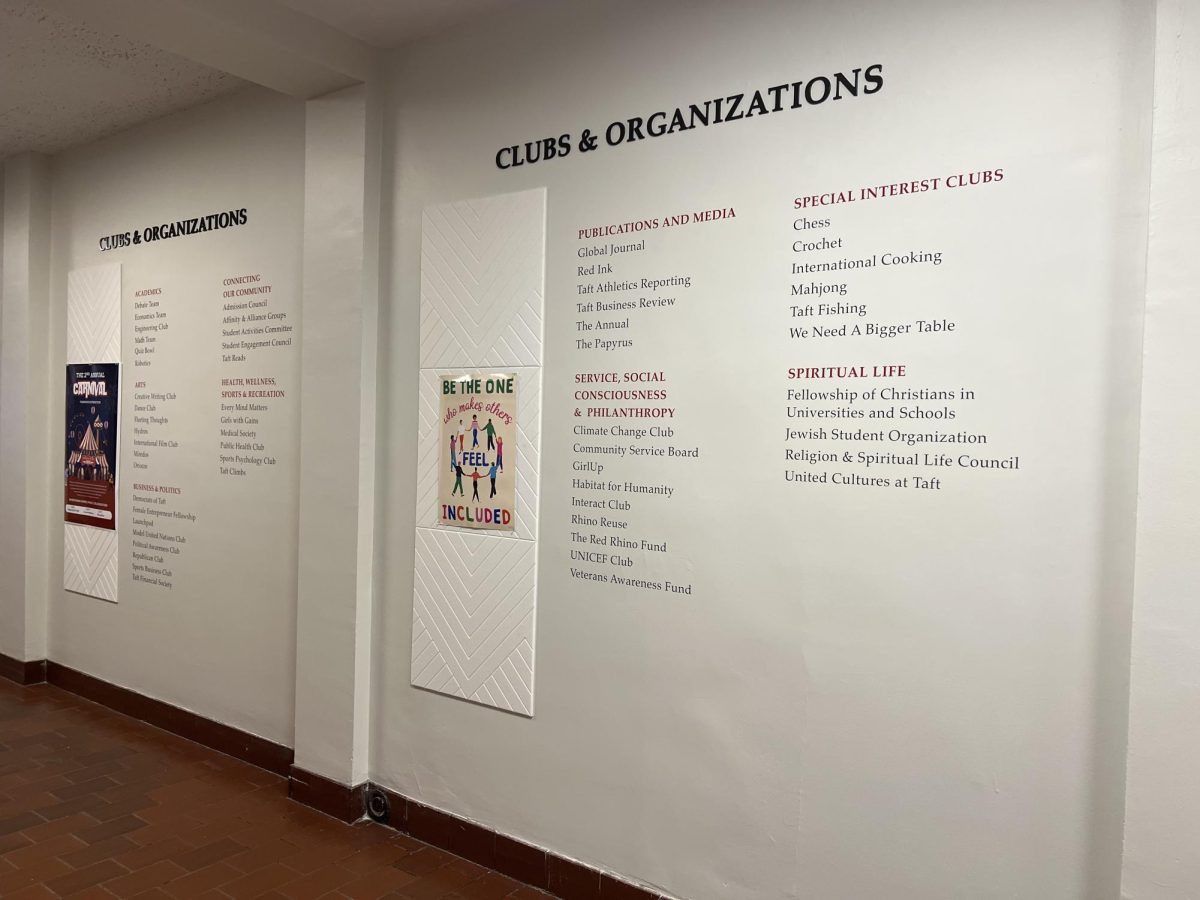

Yet despite this definition, many students still feel unsure of how our leadership systems actually function. At other boarding schools, student governments often include defined roles like president or vice president, with formal campaigns, platforms, and structured opportunities to influence school policy. At Taft, our class committee system can feel far more ambiguous. In our interview with Mr. LaCasse, he described the purpose of class committees as a chance to “represent the interests of the specific class and provide an opportunity for the class to work together on things that are important to the class.” But when asked about the specific responsibilities, he admitted, “There’s not really a clear articulation about what it is that [class committees] are supposed to accomplish. It’s very much at the discretion of the class and the class deans.”

Without clarity, elections can often hinge on a person’s charm and charisma rather than their actual ideas — essentially, a “glorified popularity contest.” Underclassmen, in particular, told us they didn’t feel equipped to vote for people they had practically just met. With no speeches or campaign process, they lacked the information to engage meaningfully. To put it simply, Taft students tend to vote for the names they recognize, not the ideas they believe in. Yet, Mr. LaCasse didn’t oppose the idea of adding structure; he welcomed it. “If students want something different and can articulate the rationale for it, that’s worth discussing,” he said. He even proposed the possibility of a “constitutional convention” where students could reimagine how leadership is defined and elected. What matters most, he emphasized, is that student leadership remains rooted in community. “This really is a space where you all are responsible for what happens,” he said. “And the more that you feel agency there, the better outcome you’re going to have.”

At the end of the day, our tower of pasta looked nothing like the Eiffel Tower, but it stood. It stood because we worked together as a group, with the materials we had, and adapted. This can serve as a metaphor for how we see Taft’s leadership structure: it is a system held up by effort, tradition, and trust. One that is in the hands of the students. It is therefore up to us, to build and shape the system of student governance that represents us all: whether you believe that looks reminiscent of the format we have today, or if you envision something different. It’s up to us to decide whether class committee is just a title — or a responsibility.